1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Though it owns no buses, nor roadways, trails, or any other physical infrastructure assets, the Ulster County Transportation Council (UCTC) is the entity responsible for allocating federal funding to address the transportation needs of its planning area which consists of all of Ulster County. Among many other needs, funding through UCTC keeps Ulster County’s buses running, roads paved, infrastructure safe, trails in good condition, and helps chart the county’s course going forward – understanding its history, where it stands, and how it can continue to improve for those who live, work, and visit Ulster County.

One of UCTC’s responsibilities is the preparation and adoption of a Long Range Metropolitan Transportation Plan (LRTP). The LRTP must look at least twenty years into the future and be updated at no less than five-year intervals. This long look forward is particularly valuable as transportation facilities can take a long time to move from idea to plan to design and construction, and then once introduced they are long-lasting. This LRTP, called Mobility 2050, is a strategic vision of Ulster County’s transportation future, the policies necessary to support that vision, and an investment plan for its implementation.

Dynamic Planning Environment

There are several critical issues that have impacted the development of this LRTP, including:

Federal Transportation Authorization

The current federal surface transportation law, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), expires in 2026. Priorities of prospective future legislation are not yet known.

Federal Transportation Funding

A significant proportion of capital funds in New York State’s transportation program come from the federal the Highway Trust Fund (HTF), which is underfunded.

State and Local Transportation Funding

The New York State Dedicated Highway and Bridge Fund has fiscal challenges, related to substantial debt service payments resulting from past borrowing, and use for non-capital purposes. Local governments do receive state funds but must rely primarily on property tax and sales tax receipts to pay for transportation projects that are not on the federal-aid road system.

Aging Infrastructure

Like much of the rest of the country, our state’s roads and bridges, transit systems, and railroads are characterized by aging infrastructure.

Focus On Freight and Economic Development

The trend in federal transportation policy over recent years is to pay more attention to freight movement and how it supports regional, statewide, and the national economy.

Changing Attitudes About Land Use

Whether urban or suburban, people increasingly seek a human scaled neighborhood that is walkable and bikeable, has access to schools and shopping, and has convenient public transit.

Transportation and Harmful Air Pollution

UCTC continues to monitor the policy landscape relating to air pollution and seeks opportunities to further reduce the transportation system’s contribution to air pollution.

Public Health and Active Transportation

The public health community has begun to turn its understanding of the value of physical activity into participation through calls for active transportation initiatives and opportunities.

Transportation and Technology

A twenty-five-year planning cycle is a very long time in today’s environment of fast changing technology, disruptor business models, environmental challenges, and economic cycles.

Please see p. 7 of the LRTP for a more detailed discussion of these issues.

Federal Planning Requirements

The framework of the LRTP is codified in Titles 23 (FHWA) and 49 (FTA) of the Code of Federal Regulations. The LRTP must address the following ten planning factors:

- Support the economic vitality of the metropolitan area, especially by enabling global competitiveness, productivity, and efficiency;

- Increase the safety of the transportation system for motorized and non-motorized users;

- Increase the security of the transportation system for motorized and non-motorized users;

- Increase accessibility and mobility of people and freight;

- Protect and enhance the environment, promote energy conservation, improve the quality of life, and promote consistency between transportation improvements and State and local planned growth and economic development patterns;

- Enhance the integration and connectivity of the transportation system, across and between modes, for people and freight;

- Promote efficient system management and operation;

- Emphasize the preservation of the existing transportation system;

- Improve the resiliency and reliability of the transportation system and reduce or mitigate stormwater impacts of surface transportation; and

- Enhance travel and tourism.

Related Plans

UCTC is also required to integrate into the LRTP the goals, objectives, measures, and targets contained in related transportation plans developed and adopted by state departments of transportation and public transportation providers.

Please see p. 10 of the LRTP for a list of related plans.

Title VI Of the Civil Rights Act

UCTC support for and compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act can be found in the following:

- Evaluation measures built into the Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP) and Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) project selection process;

- The use of Geographic Information System (GIS) resources to illustrate the relationship between transportation investments programmed and areas with concentrated low-income, minority, age 65 and older, and mobility disability populations;

- Outreach for UPWP projects that recognize the needs of the Limited English Proficiency (LEP) population including Spanish translation of project outreach materials, inclusion of Spanish translators at public outreach events and meetings and holding meetings in locations that serve the LEP population; and

- Focusing UCTC transit planning efforts on the needs of underserved areas and populations.

About UCTC

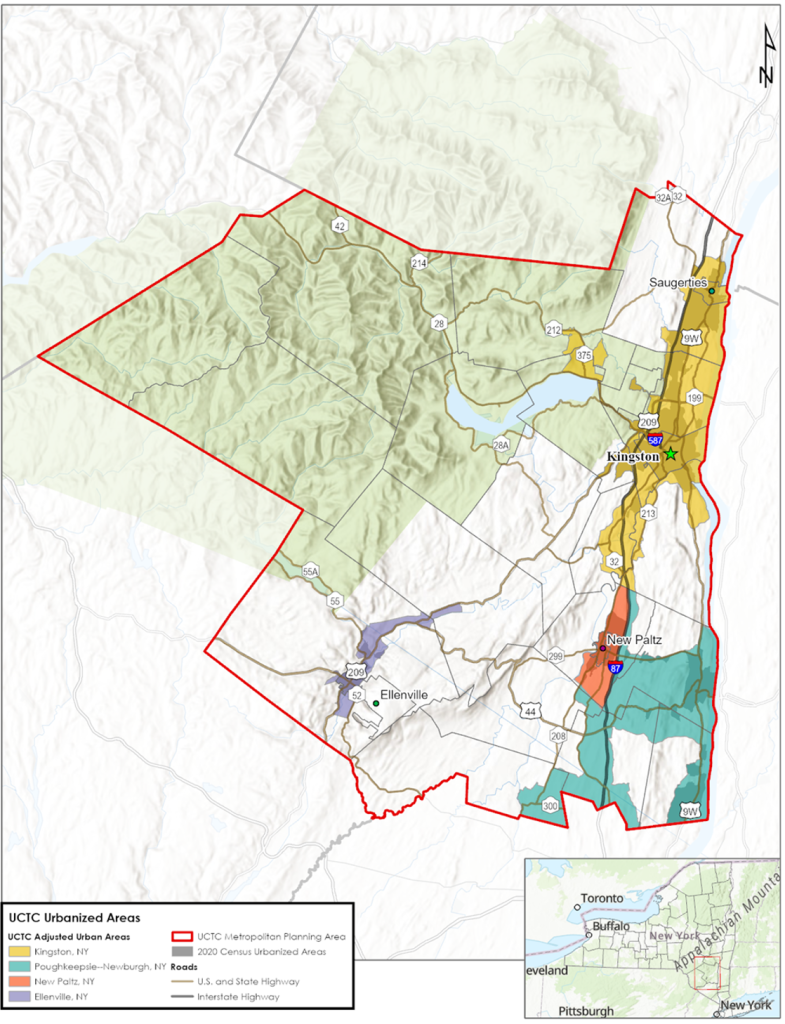

The Kingston urbanized area has more than 50,000 people as determined by the U.S. Census Bureau. Federal regulations require that every urban area in the United States of more than 50,000 persons have a designated MPO in order to qualify for Federal highway and transit funding. UCTC in its role as MPO provides the forum for cooperative transportation decision making for the metropolitan planning area.

The UCTC’s decision-making authority rests with its Policy Committee voting members. The Policy Committee is supported by an advisory Technical Committee which monitors the operational aspects of the UCTC planning program for consistency with Federal, State, and local planning requirements, reviews technical and policy-oriented projects and programs, makes recommendations to the Policy Committee for consideration, and monitors the activities of UCTC staff.

Please see p. 11 of the LRTP for a full list of UCTC Membership.

Mid-Hudson Valley Transportation Management Area

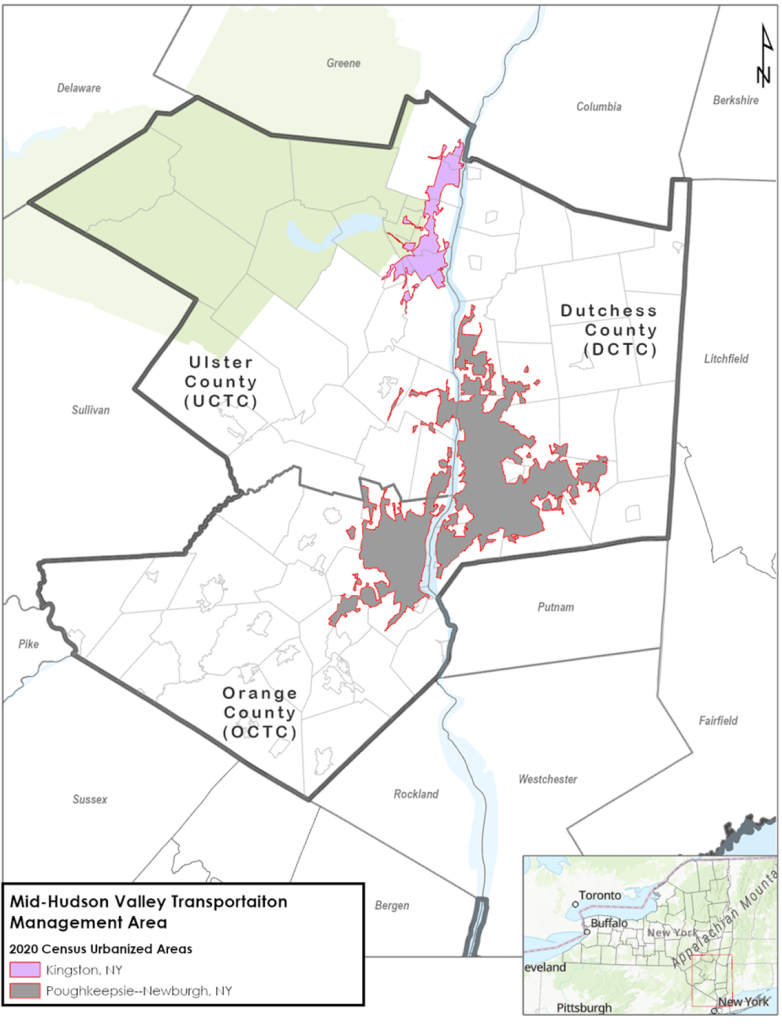

As an urbanized area with a population of over 200,000, the Poughkeepsie-Newburgh urbanized area (including portions of southeastern Ulster County) is classified as a Transportation Management Area (TMA), which means it is subject to additional Federal requirements and scrutiny. The fusion of the three counties of the Poughkeepsie-Newburgh urbanized area (Dutchess, Orange, and Ulster counties) into a single planning area is known as the Mid-Hudson Valley TMA.

The TMA is governed collaboratively by three separate MPOs – the Dutchess County Transportation Council (DCTC), the Orange County Transportation Council (OCTC), and UCTC. The three MPOs meet regularly concerning TMA requirements, and coordinate on work activities such as planning studies, TIP development, long range transportation plans and other work products that impact the region.

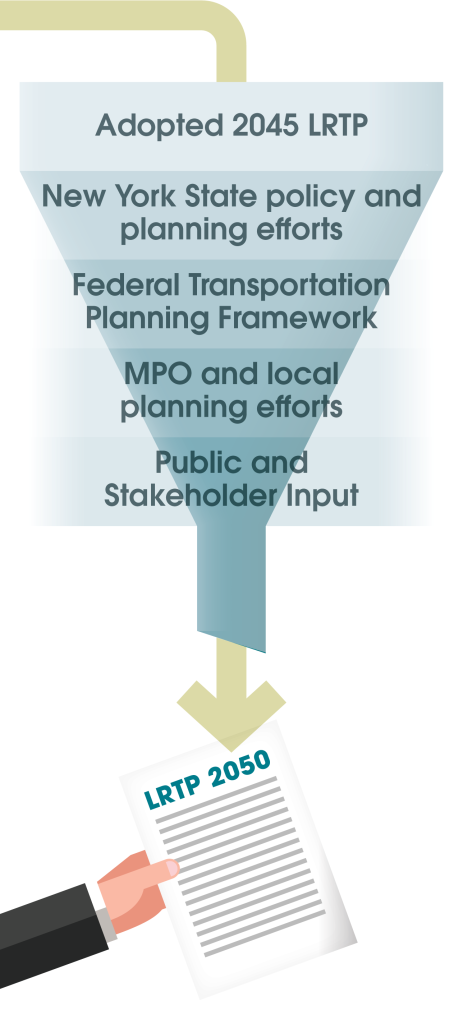

2050 LRTP Development Process

Mobility 2050 builds on the adopted 2045 LRTP, the “related plans” from other agencies and the initiatives at the state level regarding the environment, resilience, and emerging active transportation trends. Public input on the LRTP also played important role in its development.